Does

exercise influence the body’s internal clock? Few of us may be

conscious of it, but our bodies, and in turn our health, are ruled by

rhythms. “The heart, the liver, the brain — all are controlled by an

endogenous circadian rhythm,” says Christopher Colwell, a professor of

psychiatry at the University of California, Los Angeles’s Brain Research

Institute, who led a series of new experiments on how exercise affects

the body’s internal clock. The studies were conducted in mice, but the

findings suggest that exercise does affect our circadian rhythms, and

the effect may be most beneficial if the exercise is undertaken midday.

For the

study, which appears in the December Journal of Physiology,

the researchers gathered several types of mice. Most of the animals

were young and healthy. But some had been bred to have a malfunctioning

internal clock, or pacemaker, which involves, among other body parts, a

cluster of cells inside the brain “whose job it is to tell the time of

day,” Dr. Colwell says.

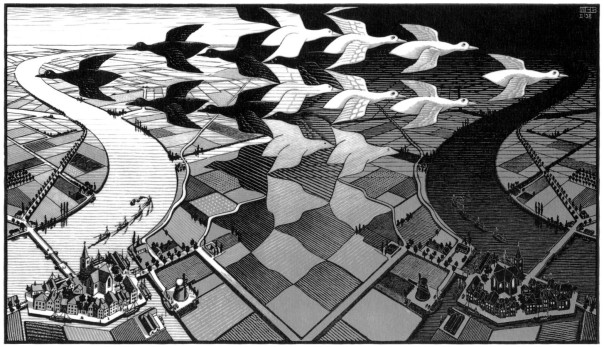

These pacemaker cells receive signals from

light sources or darkness that set off a cascade of molecular effects.

Certain genes fire, expressing proteins, which are released into the

body, where they migrate to the heart, neurons, liver and elsewhere,

choreographing those organs to pulse in tune with the rest of the body.

We sleep, wake and function physiologically according to the dictates of

our body’s internal clock.

But, Dr. Colwell says, that clock can

become discombobulated. It is easily confused, for instance, by viewing

artificial light in the evening, he says, when the internal clock

expects darkness. Aging also worsens the clock’s functioning, he says.

“By middle age, most of us start to have trouble falling asleep and

staying asleep,” he says. “Then we have trouble staying awake the next

day.”

The consequences of clock disruptions extend beyond

sleepiness. Recent research has linked out-of-sync circadian rhythm in

people to an increased risk for diabetes, obesity, certain types of

cancer, memory loss and mood disorders, including depression.

“We

believe there are serious potential health consequences” to problems

with circadian rhythm, Dr. Colwell says. Which is why he and his

colleagues set out to determine whether exercise, which is so potent

physiologically, might “fix” a broken clock, and if so, whether

exercising in the morning or later in the day is more effective in terms

of regulating circadian rhythm.

They began by letting healthy

mice run, an activity the animals enjoy. Some of the mice ran whenever

they wanted. Others were given access to running wheels only in the

early portion of their waking time (mice are active at night) or in the

later stages, the equivalent of the afternoon for us.

After

several weeks of running, the exercising mice, no matter when they ran,

were found to be producing more proteins in their internal-clock cells

than the sedentary animals. But the difference was slight in these

healthy animals, which all had normal circadian rhythms to start with.

So

the scientists turned to mice unable to produce a critical internal

clock protein. Signals from these animals’ internal clocks rarely reach

the rest of the body.

But after several weeks of running, the

animals’ internal clocks were sturdier. Messages now traveled to these

animals’ hearts and livers far more frequently than in their sedentary

counterparts.

The beneficial effect was especially pronounced in those animals that exercised in the afternoon (or mouse equivalent).

That

finding, Dr. Colwell says, “was a pretty big surprise.” He and his

colleagues had expected to see the greatest effects from morning

exercise, a popular workout time for many athletes.

But the

animals that ran later produced more clock proteins and pumped the

protein more efficiently to the rest of the body than animals that ran

early in their day.

What all of this means for people isn’t clear,

Dr. Colwell says. “It is evident that exercise will help to regulate”

our bodily clocks and circadian rhythms, he says, especially as we enter

middle age.

But whether we should opt for an afternoon jog over one in the morning “is impossible to say yet,” he says.

Late-night

exercise, meanwhile, is probably inadvisable, he continues. Unpublished

results from his lab show that healthy mice running at the animal

equivalent of 11 p.m. or so developed significant disruptions in their

circadian rhythm. Among other effects, they slept poorly.

“What we

know, right now,” he says, “is that exercise is a good idea” if you

wish to sleep well and avoid the physical ailments associated with an

aging or clumsy circadian rhythm. And it is possible, although not yet

proven, that afternoon sessions may produce more robust results.

“But

any exercise is likely to be better than none,” he concludes. “And if

you like morning exercise, which I do, great. Keep it up.”